When I first started this blog page, I had a great response from the brilliant Aimee Tinkler asking how I thought belonging might affect the learners brain in the classroom and whether developing a strong sense of belonging in our students might release additional mental capacity for learning?

This is a great question, and one that I have given a great deal of thought to since then. In order to answer this, I think a good place to start would be to understand a little bit more about Cognitive Load Theory.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) was a term coined by Sweller in 1988. I will attempt a brief summary here, but for a more full understanding, it is well worth exploring some of the articles found here in Science Direct.

Essentially, CLT identifies the conscious processes of thinking as working memory and asserts that, there are limits to the capacity of these processes. Once new information has made it in to our working memory, it then requires rehearsal and retrieval in order to be cemented into our, potentially limitless, long term memory. Our brain files new information in schemas of inter-related information. The more we practice retrieval from these schemas, the more secure the learning will become.

If our cognitive processes are overloaded, our brain is no longer able to take in information, thus rendering learning impossible. It encourages teachers to consider the cognitive load of their students in designing and administering tasks, and to aim to optimise conditions in order to allow full and focused cognitive activity on the intended learning outcome.

Sweller identified three main types of cognitive load on our students that effect the operational capability of our working memory.

Intrinsic – This refers to the complexity of the subject matter itself. ie, fully understanding the theory of cognitive loading, is more complex than a simple addition sum, such as 2+2=4. Whilst the teacher can do little to manipulate the complexity of the material, they should be aware of it when introducing concepts.

Extraneous – This area of cognitive load is increased by the impact of outside factors that may not be connected to the learning at all. These could be environmental factors, such as noise, or distracting displays, or they could be physical factors, such as hunger, or anxiety. Teachers are encouraged to do as much as they can to limit extraneous factors when delivering intrinsically complex learning tasks.

Germane – This third area of cognitive load is created by the generating of new schema, or the lack of prior, or related, knowledge on a topic. For example, if you were suddenly dropped in to a lecture on micro biology, with no prior experience in this area, your brain would be so overloaded trying to make sense of all of the new information, you would likely retain none of it. However, if you had already built a schema of prior knowledge on micro biology within which to reference the new knowledge, you would be much more likely to retain it.

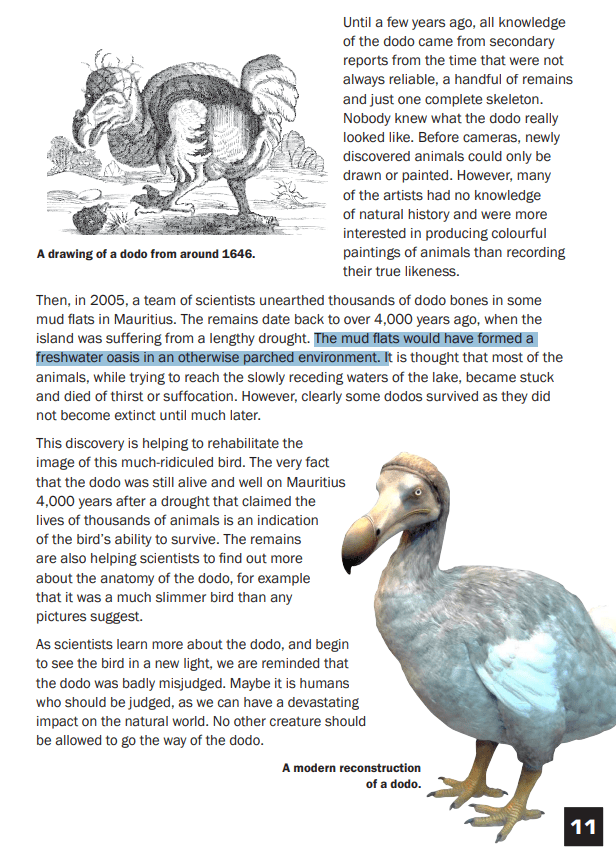

I once watched Christine Counsell give a great explanation of how the development of schema opens doors to learning and understanding what would otherwise be closed to our most disadvantaged students. She referenced the 2016 Year 6 SATs reading paper below. (administered to 10-11 year olds in the UK)

In order to make sense of the highlighted sentence, a student would have to already have a schema giving them prior knowledge of what is a ‘mud flat,’ what do we mean by the word ‘formed,’ what is an ‘oasis,‘ what do we mean by ‘parched,’ and additionally, ‘environment.’ If we are aware that our working memory can only hold around 7 pieces of information at once, without this schema being pre-populated in our mind, we would stand no chance of being able to interpret this sentence, let alone the rest of the report. We could perhaps decode it, but it would not remain in our working memory.

This is a great example of where exposing our students to cultural capital pays dividends across all areas of learning.

So, now that we know a little more about Cognitive Load theory, what has this got to do with Belonging?

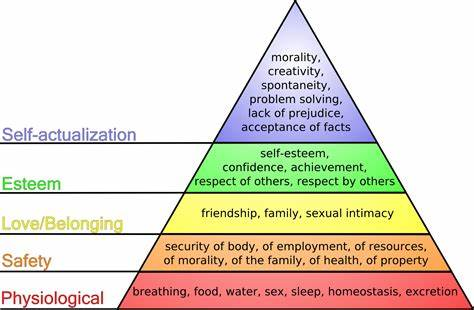

If we go back to the start, in my blogpost ‘A tale as old as time.’ we can see that belonging is found pretty high up on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

That is to say that it is a basic need that needs fulfilling in order that we are able to function effectively. If we are unable to fulfil these needs, we will be constantly seeking ways in which we might be able to do so.

If a child came in to our classroom hungry, we know that in order for them to learn, we would need to satisfy that basic need. That is why we run breakfast clubs, especially in a testing week! We want to minimise distraction, or ‘Extraneous‘ load. When a student is lacking any of the basic needs identified by Maslow, research tells us that they will feel under threat.

Without food, water, sleep, security, friendship or self esteem, our brain feels the need to seek out these basic needs above all else, it feels threatened by their absence and so, why would learning matter?

We could deliver the most brilliant lesson, with the most amazing resources, in the most wonderful environment, but it will never be remembered by the child whose basic needs remain unfulfilled. As a wise colleague said to me only this week, ‘a rising tide may indeed lift all boats, but if the boat is full of holes, it won’t be floating for long.‘ (I’m quoting that as Sue Costello, even if she nicked it from somewhere else.)

When children feel safe and connected in their learning environment, they are freed up to truly explore their potential; for it is only when basic needs are met that true growth can occur. Lael Stone

So, if a child is not experiencing a sense of belonging in your classroom, they are likely to be seeking it. Typically, a child will seek to find their sense of belonging by reverting to actions that will give quick, satisfying responses, affirming they are good at something, that they have a place, a role, a purpose. For some, that may be by working hard and trying to seek positive affirmation from the teacher, but for others it could be cheap laughs, confrontation or withdrawal. But, whatever it is, positive or negative, it is distraction from the task at hand, the learning intention of the lesson. It is eating up their extraneous cognitive load!

In order to reduce cognitive load for our students, we need to focus on the sense of belonging that is generated in our classroom for ALL, alongside running the breakfast club!

If you read my blogpost, ‘My Best Bets for Belonging.’ you may get a few ideas as to how you might consider this in your day to day planning.

Sadly, not every child comes in to our classroom ready to learn. As educators, we need to consider the wider picture and plug the holes to give our students the greatest chance of success.