The value of Respect is one that you will find across cultures, across institutions and across countries. The United Nations identified it as one of the top 10 values shared across cultures and Gocke (2021) identified it as fifth in the core values necessary in education, as identified by future educators. But why? What does it mean, why is it there and, perhaps most importantly, are we all talking about the same thing?

When you look for a definition, you will find that it is generally found to mean one of two things in an educational setting. Firstly, it could mean, ‘a feeling of deep admiration for someone or something elicited by their abilities, qualities, or achievements,’ or it could be taken to mean, ‘having due regard for the feelings, wishes, or rights of others.’ It is commonly taken to mean having due respect for another religion or culture and it is frequently referenced in terms of having respect for the property of others. Perhaps most commonly in schools, it is also used to state that we should follow the instructions of adults, having ‘respect‘ for their authority.

But there is a Tolstoy quote that has always resonated with me. ‘Respect was invented to cover the empty space where love should be.’

What did he mean by this? He meant that where love exists, you don’t need to ask for respect, it is unnecessary, or even meaningless. Take Aretha Franklin as a further example, ‘ALL I’m asking for, is a little respect.’ It is the very MINIMUM she expects from a healthy relationship, so why would it be the aspiration of our schools?

If we take first the potential meaning, that schools use it to ask students to show a deep admiration for someone’s abilities, qualities or achievements, this cannot be demanded through our school culture. This kind of respect is earned, it is triggered by our emotional response to someone’s persona, or achievements. We can teach students to recognise the value in others and we can give them the opportunity to be exposed to a wider life outside their own so that they an appreciate it, but we cannot demand that they admire it.

If we take the second meaning i.e. having due regard for the feelings, wishes or rights of others, here’s where I think, as educators, we are aiming too low. Coming back to Tolstoy, if we felt love towards those who make up our school community, there would be no need to respect their feelings, or rights, it would be implicit, it would be automatic, it would just be part of the way we respond to others.

Love is a word that we don’t use often enough in education. It feels outdated, or perhaps even amusing, to speak of it in relation to our school community but, when I read John Tomsett’s Love over Fear I realised that in schools is exactly where this word belongs. In his ode to values driven education, Tomsett explores the impact of genuine care and love for students, staff and community, showing that this, above all else, makes the difference to student success.

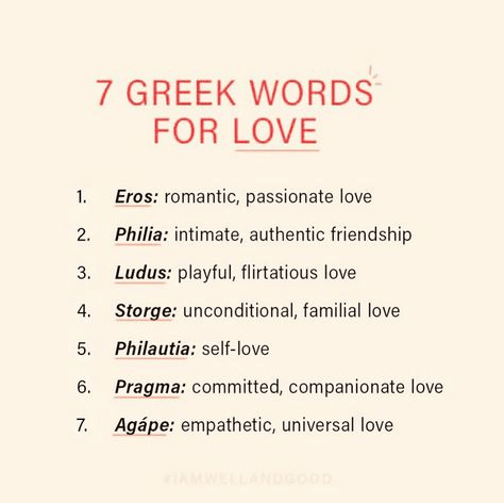

One of our problems here in the UK, is that we only have one word for love and, a bit like respect, it has multiple meanings. In Greek however, they have seven!

Agape, a universal, empathetic love for others. A wish to see them succeed, to flourish and to support them when they might stumble. This is how we should be educating our children. Teaching them that mutual love for their peers, their teachers and their community, is the key to finding our own happiness and success.

Next to this, respect feels somewhat divisive. It amplifies difference, it encourages us to see the differences in others but accept that that is ok, it’s something that we should put up with, because we can’t help all being different. That is all very well, but in a community bound by love, we would truly celebrate diversity, not just accept it, and don’t get me started on the word ‘tolerance!’ How poor a word to describe our interactions and relationships with others. To tolerate really is, in essence, having to endure something that you don’t like because you know that you should.

What’s more, love is not a value that you can insist on. You have to work hard to establish a school founded on love. It takes genuine care, deep empathy and a lot of our time. If we don’t place it publicly high on our agenda, it will fall away, after all, we know that in a profession that feels the pressure of time like no other, we only make time for that which we value.

I do accept that, in a divided community, the values of respect and tolerance are a good stepping stone on the journey, a sticking plaster to overcome difficult environments and poor relationships, but they should not be our final destination. The final destination should be a harmonious school community, bound together through a strong sense of love and belonging, and surely our value statements should reflect our ultimate goal, not the journey we are on.

So let’s not do a disservice to our students and communities by focusing on bridging division through respect and tolerance. Let us instead focus on building a community with it’s foundations in love and shared vision. Let’s explore difference through our inquisitive nature, love our neighbours for the richness they bring to our life and show a universal love that embraces all so that we can flourish in an environment in which we feel we truly belong.